The Big One awaits

This month, I am starting my fourth and final year of the Basic Program of Liberal Education for Adults at the University of Chicago’s Graham School. The Basic Program is an open enrollment, non-credit, four-year sequence of courses featuring the close reading and discussion of what have been called the Great Books. It starts with works by ancient Greek philosophers and poets (e.g., Plato, Aristotle, Homer) and proceeds to examine other canonical authors and works of the Western tradition (e.g., Shakespeare, the Bible, Kant).

Here’s how the Basic Program describes itself:

The Basic Program of Liberal Education for Adults is a rigorous, noncredit liberal arts program that draws on the strong Socratic tradition at the University of Chicago and covers the foundations of Western political and social thought.

***

The starting point for the Basic Program is the Four-Year Core Curriculum. Each year is made up of three 10-week Quarters. New Students begin in Year 1 Autumn. They choose from morning, afternoon, or evening sections held online and earn a certificate upon completion of the entire curriculum.

***

Each section meets for three hours once a week. Class sections consist of: a 90-minute seminar (discussing several texts) with one instructor, a 90-minute tutorial (discussing a single text) with a different instructor, with a 15-minute break in between.

Bucket listed

I had long considered studying the Great Books a personal bucket list item, a significant piece of unfinished business in my education. My undergraduate school, Valparaiso University, is home to an excellent honors college built around the Western canon. But after sampling two of its literature courses as a not very intellectual post-adolescent, I just wasn’t interested in that course of study. But over the years, I began to feel an increasingly strong tug to give these books a try. On occasion, I would try to read some of these great works on my own. These soon-halted efforts taught me that it wasn’t going to happen outside of a more structured learning environment.

I assumed that retirement might provide me with that opportunity. But perhaps there’s nothing like a global pandemic to help you identify and prioritize your options. I had known of the Basic Program for many years. However, originally it was offered only via in-person classes in Chicago, which precluded my enrollment given my Boston residence. Then, during the summer of 2020, I learned that the Basic Program was being offered online, so I quickly investigated.

Even though there are no papers, quizzes, or exams, class sessions are built around expectations of significant student participation. So if I wanted to make the most of this opportunity, I knew that fairly beefy weekly reading assignments would be part of the deal. Although I quickly grasped that this would be a major commitment — for four years, no less — it was an easy decision to sign up.

I now have three years of the Basic Program under my belt. It has been a stimulating, intellectually rewarding experience. I have enjoyed my fellow students and our instructors. The Program has also required a lot of brain work! During busy times with my own work and philanthropic obligations, keeping up with the reading has been challenging. On occasion I’ve made it to class having basically skimmed the material, which is wholly inadequate preparation for two 90-minute sessions featuring intense and close examination of classic texts. But I’ve never regretted enrolling for a minute.

At some point, I will write more about my overall experience in the Basic Program. For now, if you’re curious about what a typical year’s reading in the Program looks like, here is the first-year curriculum. The three colors represent the autumn, winter, and spring quarters. The titles with a banner are for our tutorial courses, which means we spend the entire term on that book alone. The remaining titles are for our seminar courses, which means we cover all or parts of those books, in a more brisk fashion, during the term. (Hamlet, by the way, was our cohort’s Shakespearean tragedy.) For more about the full four-year curriculum, please go here.

“Senior year” beckons

Soon I will join fellow students in our cohort via Zoom to begin what some of us are humorously calling our senior year. In some ways, it feels like we’ve been on quite a journey together already.

During the autumn quarter, our tutorial sessions will be devoted to Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War, written during the late 5th century B.C. This book is a foundational work of history and international relations, chock full of insights relevant to contemporary events. It is required reading at the U.S. military war colleges because of the lessons it holds for understanding modern statecraft.

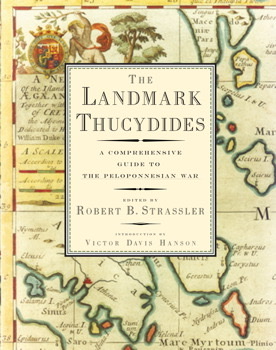

Thucydides has ranked high on my bucket list of books for many years, but an attempt to read it on my own years ago left me rather intimidated. That’s why I was delighted to see it on the Basic Program reading list, knowing that I will benefit from reading and discussing it with my classmates and instructor. We’ll be using a much-praised edition, The Landmark Thucydides (1998), edited by Robert Strassler, that includes not only a highly respected translation of the primary text, but also lots of supplementary material to fill in our understanding of the pertinent cultural and political dimensions of ancient Greece.

What else is on the reading list for this term? Our seminar sessions will cover Plato’s Symposium, selected chapters from Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, and Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Although I encountered the Symposium in college, the other two authors and books are new to me.

And so, a busy “senior year” approaches, to be juggled along with work and other commitments. I hope it is a satisfying and enjoyable journey.