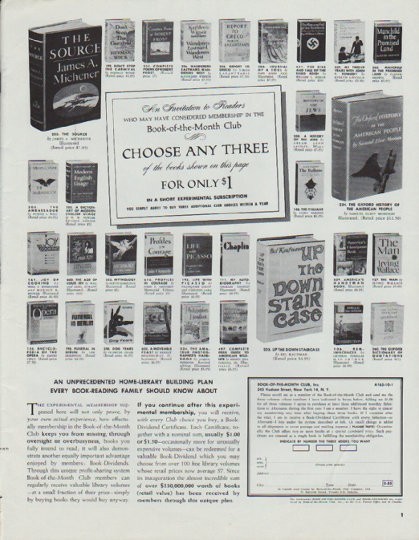

1965 BOMC ad

Not long ago, if you were part of America’s growing middle class and wanted to expand your cultural literacy, the Book-of-the-Month Club (BOMC) was a popular option towards doing so.

Founded in 1926, BOMC was the brainchild of New York ad agency guys who tapped into America’s embrace of mail order and the reading appetites of its upwardly mobile middle class. People typically became BOMC members by answering a magazine ad or a direct mail invitation. The Club’s marketing hook was an initial membership package that offered either a free premium volume or allowed you to select titles from the club’s catalog for a small initial sum. However, you also had to fulfill a membership agreement, which meant buying a specified number of books at club prices within the next two or three years.

Every month, members would receive a packet in the mail, containing a flyer describing the editors’ main selection for that month, a short catalog describing alternate and back list selections, and a reply card. If you did nothing, the main selection would be sent to you. You could also use the reply card to indicate that you didn’t want the main selection or to order alternate and back list selections.

Here’s a premium book once offered to new BOMC members, a 1954 illustrated profile of Europe. I can only imagine the different emotions evoked by this volume, published just nine years after the conclusion of the Second World War.

(photo: DY)

BOMC as a middlebrow cultural broker

BOMC offered a way to bring good books into your home with minimal hassle, screened by reviewers who had discerning eyes for the reading tastes of middlebrow America. Over the years, BOMC assembled various panels of judges to evaluate and select books for its catalog, some of whom were accomplished authors in their own right. During the Club’s heyday, serving as a BOMC selection committee judge carried some prestige within mainstream publishing circles.

Commercially speaking, BOMC was a big deal to authors seeking to broaden their readership. Main selection status signaled a stamp of approval by a trusted brand and a guarantee of higher sales. BOMC favored quality fiction and non-fiction for a general, intelligent audience, while largely avoiding books that might be considered too tawdry or cheesy. Its marketing campaigns played on such appeal and the idea of building a good home library, while usually managing to avoid lapsing into higher-level snobbery.

Among some stuffier types, however, this combination of commercial advertising and middle class reading tastes prompted derision of the whole enterprise (and by implication, perhaps, of its customers). Nevertheless, the Book-of-the-Month Club elevated America’s literary intelligence by bringing good books to an upwardly mobile swath of America’s population.

BOMC bestseller

If you’re looking for a sign of where BOMC’s cultural center of gravity rested during its heyday, consider that its bestselling book ever was journalist William Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany. First appearing in 1960, it was a publishing phenomenon, stunning industry experts who believed that Americans wanted to put anything to do with the war behind them. The Rise and Fall was a BOMC main selection and a favorite backlist choice for years to come.

(photo: DY)

Big box and online booksellers

Predictably, the appearance of larger, brick and mortar bookstores and the emergence of online booksellers would spell trouble for the Book-of-the-Month Club. I was an off-and-on member from the 1980s through the early 2000s, and I witnessed its steadily declining commercial and cultural significance in shaping reading appetites.

After briefly shutting down in 2014, BOMC quietly reappeared the next year. Its owner, Bookspan, relaunched the Club as a fully online enterprise, using a streamlined subscription model. Its target readership is younger women who enjoy popular fiction.

When more is less special, and less is more special

I sometimes think about BOMC’s classic sales model as I try to manage my personal and professional book collections.

I’m generally careful in my personal spending, except for when it comes to buying books. On that note, I have little willpower. I can justify rationalize a book purchase on multiple grounds: (1) I want to read it now; (2) I want to read it later; (3) I might want to read it later; (4) It’s on sale; (5) It’s a used bookstore bargain find; (6) It’s useful for my work; (7) It’s a lovely edition of a favorite book; (8) Whatever. As a result, I have many more books than I could ever hope to read, even assuming a comfortable retirement someday and many healthy years to follow.

I’m grateful that I can afford to indulge my book-buying habit. I realize, however, that adding multiple books to my home and office libraries each month is not as special as the delicious anticipation of a new book, selected from a curated list. For example, I wonder how cool it was for a hungry reader to receive Marchette Chute’s Shakespeare of London (1949), including a neat little essay accompanying the volume.

(photo: DY)

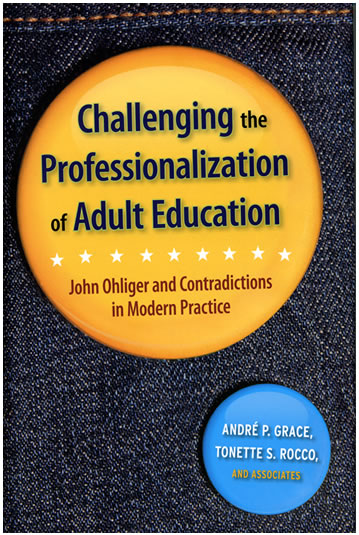

Highly recommended

I won’t burden you with further observations about BOMC’s place in America’s 20th century cultural history. If you want to learn more about that story, with a big dollop of personal reading memoir mixed in, then I highly recommend Janice Radway’s A Feeling for Books: The Book-of-the-Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle Class Desire (1997). Ignore the snarky reviews by those who, for some reason, can’t get over (1) a book that’s good with middlebrow culture; and (2) BOMC’s undeniable profit-making motive. This is an informative and entertaining read.

(photo: DY)

***

Note: Passages from this post were adapted from a 2016 entry to my personal blog, Musings of a Gen Joneser.